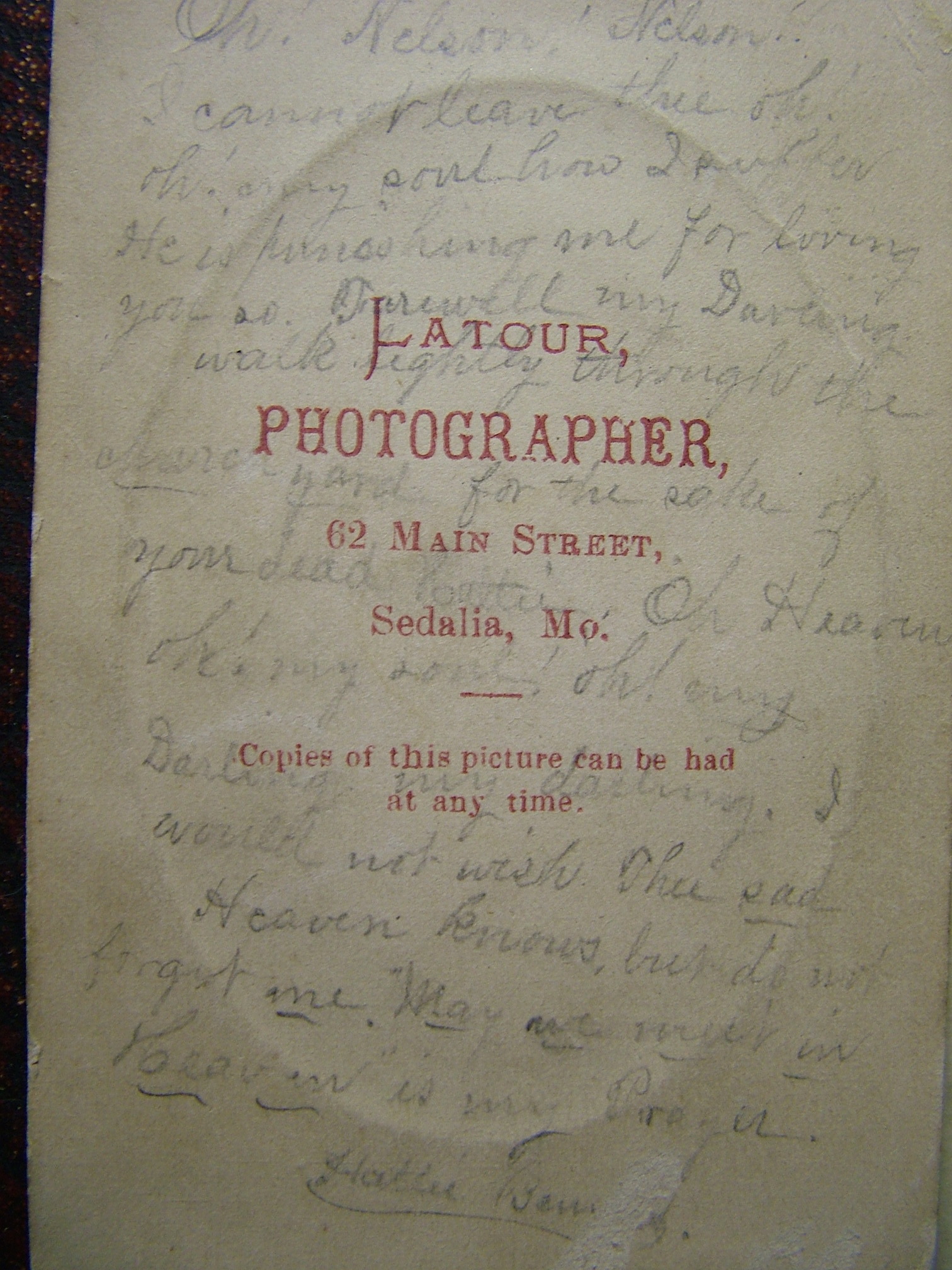

Written on the back of the palm-sized carte vista photograph, her words called out like pleas. Her fingers, arguably shaking, somehow managed to produce a scrolled message to her husband, George Nelson Bennett. She clung to the last remnants of her educated status with a penmanship, practiced and perfected throughout her forty-four years, writing:

“Oh, Nelson, Nelson. I cannot leave thee oh! oh! my soul – how I suffer He is punishing me for loving you so. Farewell my Darling. Walk lightly through the church yard for the sake of your dead Hattie, Oh Heaven, Oh! my soul! Oh! my Darling my darling. I would not wish thee sad. Heaven  knows, but do not forget me. May we meet in Heaven is my Prayer. Hattie Bennett.”

knows, but do not forget me. May we meet in Heaven is my Prayer. Hattie Bennett.”

Hattie punctuated her last words with a bullet fired from a pistol in a Saint Louis hotel.

It was in 1894. Hattie left her home in Pierce City, Missouri under the pretense of attending a parade and dance in St. Louis. It was there in the rented room that Hattie lived the last few days of her life and ended with a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Only weeks before she and her husband hosted an extravagant party replete with dancing and dining to celebrate their twentieth wedding anniversary. Hattie Felix met George Bennett in Kansas after the Civil War. They moved to the small southeastern Missouri town where Hattie and her husband joined the Congregational Church and garnered memberships into in several women’s societies. She owned business properties in her own name. She accessorized her wardrobe with diamonds and set her table with silver and Haviland china while hosting guests in the home that she and George shared together. She embodied what some might call an envied economic and social status that many from the small railroad town might only dream of reaching.

It is difficult to understand why Hattie chose to mark the end her forty-four years of life in a hotel far from home or what sufferings preyed upon her. What events caused such a dramatic choice? Hattie was an active participant in a place and time in America’s history. The topography and the lives lived by native-born as well as the migrators coming from the east were changing the midwestern landscape at lightning speed. Cartographers worked at a frantic pace, adding zipper-like hash marks to show the emergence of the railroad to their maps, publishing them in atlases in America and abroad. These iron-zippered markings alluded to the very real changes taking place on the land that ultimately displaced many long-standing communities for the sake of the new arrivers. Hattie’s life, too, was changing. It began and ended in this transitional space where the “new spirits” of change shaped American life.[1] Hattie, and women like her noticed the shifting of their own sexuality, marriage, money and civic power that were very different from their mothers and grandmothers.

Over the course of the next few months you can visit my blog where I will highlight a few of the many events of Hattie’s life. The casual nature of blogging allows me to take a divergent journey to explore the events influencing this Victorian woman and is separate from my dissertation study of Scottish women who migrated to places throughout the Atlantic. Hattie’s death, though tragic, is out-distanced by the interesting life details she leaves behind and is certainly worth the detour.

Over the course of the next few months you can visit my blog where I will highlight a few of the many events of Hattie’s life. The casual nature of blogging allows me to take a divergent journey to explore the events influencing this Victorian woman and is separate from my dissertation study of Scottish women who migrated to places throughout the Atlantic. Hattie’s death, though tragic, is out-distanced by the interesting life details she leaves behind and is certainly worth the detour.

A disclaimer: I became familiar with Hattie over the course of many years researching my husband’s family history. She revealed herself through various documents and I followed her trail. She is not my kin and is only remotely connected through marriage to my husband’s paternal line. Hattie and George had one son who never married and he left no children of his own. Hattie’s complex life and the people who, directly or indirectly, intersected with hers is a compelling tale and is one worth telling. Sadly, she left behind no voice to tell her story. She was a woman struggling to understand the newly forged paths that were emerging during her lifetime.

I hope to reconstitute portions of her life over the course of my next few entries, sharing some of the details of her marriage to her husband George and the child they shared together, her suicide, curious will, and the repercussions of her death on those who loved her.

[1] Rebecca Edwards offers insight to the shifting roles of women in New Spirits: Americans in the Gilded Age, 1865-1905. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Leave a Reply